The Business Stakeholders Guide to Hiring Software Engineers - Part 2

This three-part series is a guide for business stakeholders who don’t know how to conduct a technical interview for software development candidates. You don't need technical knowledge to benefit from being an observer in an interview.

This series reveals the talent acquisition hacks you need to hire the best software developers. They come in the form of a number of critical do's, don'ts, and guidelines that you should follow, which require no technical knowledge at all.

The three parts of the series are:

- Part 1: Never Allow Techs to Interview Candidates Alone

- Part 2: Avoid Coding Exercises

- Part 3: How to Assess Proficiency, Competence, and Skills

Here’s the challenge.

You have software developers reporting to you but you don’t have a coding background, so when the time comes for you to hire, you don’t know how to vet a software developer candidate. As a consequence, you’re forced to rely on currently employed software developers to conduct technical interviews for you. If this describes your situation then you’re in the right place.

This part of the series is a lesson in what not to do – coding exercises.

Avoid Coding Exercises

I get it. Coding exercises seem so logical. Shouldn’t a developer be able to prove they can code? And what better way to prove it than to have them do a coding exercise? While totally reasonable on the face of it, this line of thinking is deceptively tempting, but a terrible way to vet a candidate. There are many reasons why this is true.

The Problem of Information Asymmetry

Coming up with a suitable coding exercise takes time. Whoever does the job of creating a coding exercise has to think about the scope of the exercise, the various ways it can be solved, find or work out the optimal solution, and then consider the various angles of discussion that ensue, all of which facilitate the extraction of the candidate’s skill assessment.

But few people consider the fact that if it takes the person who creates the coding exercise two hours to invent it, for example, then how can the candidate be expected to code a solution live in fifteen minutes? In other words, for every minute a candidate is expected to code an exercise, it probably took the creator of the exercise five times as long to come up with it in the first place.

This puts the creator of the exercise at a massively unfair advantage over the candidate who is then ready to critique and challenge their performance. The candidate has to whip up their best (hopefully the optimal) solution to a problem that is very likely to be a completely new problem that the candidate has never seen before, and in a fraction of the creator’s time to boot. The creator is able to come up with the exercise comfortably and with the ability to do things like Googling stuff, whereas the candidate has no such luxuries.

Any coding exercise that an interviewer comes up with is very likely to entail information asymmetry. That is, the disproportionate amount of time and effort the creator of the exercise enjoys that the candidate does not to discover the optimal solution.

Add to that the stress and pressure of having to perform quickly, then it is clear that this is not fair. If the candidate cannot code as it is done in the real world, that is, with nobody over their shoulder, with the ability to do research, and the ability to take ample time to think about the optimal solution, then the coding exercise doesn’t produce the desired outcome, which is supposed to be an accurate representation of the candidate’s skills.

The Noisy Shadow

When a candidate is in a live coding exercise, they have to spend more time doing and less time analyzing. It is not unreasonable for them to vomit out their first attempt at the logic just to get something holistically complete before going back to review and adjust, and then repeating that cycle over multiple iterations until they have a final solution. But almost without fail the interviewer can’t help but to see the dusty mess during construction and just HAS TO start questioning and commenting, thereby completely wrecking the candidate’s train of thought and concentration.

It is already nerve-wracking to have someone shadowing you while you code at the same time you’re trying to keep track of the intricacies of the solution. So please, with all due respect, the interviewer should shut the hell up and wait until the candidate is finished if they have something to say. Furthermore, what is the point of the exercise if the interviewer steers the candidate toward a solution by asking questions in the middle of it? Isn’t that sort of hinting a form of cheating?

If you are present, as the non-technical business stakeholder, and you see this happen then you should question the interviewer’s actions. In fact, you should question the value of coding exercises entirely. But if you insist on maintaining this silly practice, at least silence the noisy shadow and teach them the value of patience. There’s plenty of time to talk about the exercise after the candidate is done. They might be surprised. It’s possible the candidate could actually produce a good solution on their own and go figure … that also happens to be the purpose of the coding exercise anyway. To demonstrate their coding abilities, not their ability to tolerate a nag.

Limitation of Scope

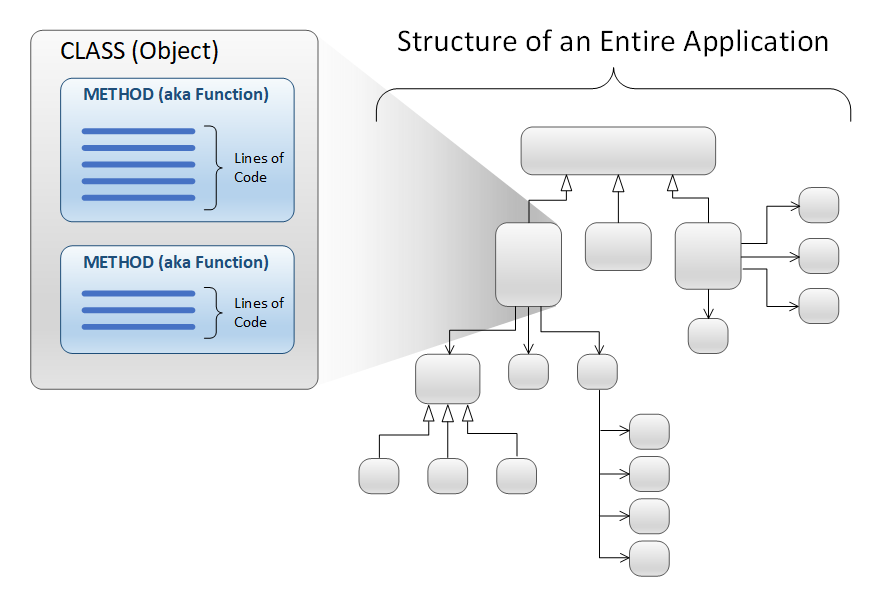

A live coding exercise can only go so far. It basically demonstrates the ability to code logic at the line level and maybe a little higher but that is not enough.

Note: For functional programming this is a bit more feasible because the next level of structure up from the individual lines of code is the function that they are in, and in functional languages, functions are the primary structure of code. So arguably, some structure can be demonstrated fairly quickly there. However, for Object Oriented languages, this is not the case.

Object Oriented (OO) languages like Java or C# involve lines of code at their most granular level, which are contained by “methods” (i.e., the OO name for functions), which are then contained by classes (and form objects), where the objects are linked through references and dependencies, which finally form the constellations of objects connected to each other, making up the application.

The more code you must produce, then the more architectural/structural decisions you have to make in the overall design of the application.

So how many levels of structure can a live coding exercise involve? I can tell you, that it’s not much. If it does involve multiple classes, it’s likely to be very simplistic. The rest of the bigger picture skills in terms of design, comprehension, trade-off judgements, cost/benefit analysis, future-proofing, and more, are not captured in a little coding exercise.

In short, the scope of a coding exercise is simply too small. It’s like judging whether you should purchase a home by looking at the interior through a peephole.

I hope that as a non-technical business stakeholder you can understand this point. The real value in a software developer shows with a holistic understanding of how to handle the design, development, testing, deployment, and maintenance of a system as a whole. Asking one to prove they can code at the line-level is so limiting that it simply doesn’t serve you well in terms of evaluating the candidate for hire.

The Plight of the Full Stack Developer

No one is at a greater disadvantage than Full Stack Developers when it comes to coding exercises. But first, what exactly is a “Full Stack Developer”? To understand what a Full Stack Developer does you have to first understand what is meant by the “stack.”

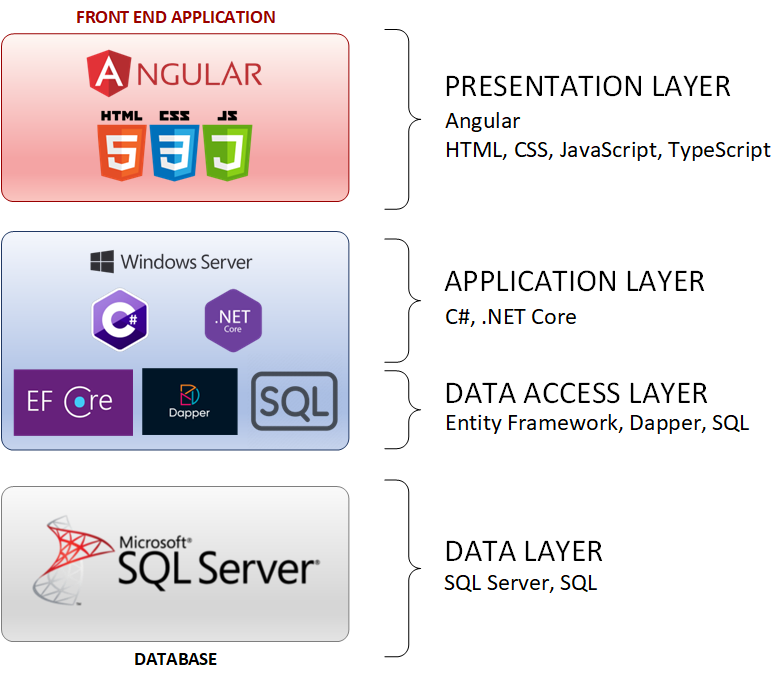

When you use a piece of software, you interact with the user interface. That is, the screens, buttons, charts, text boxes, menus, images, etc. This is the face of the application that we call the “front end.” Whatever you do to interact with the application causes parts of the application behind the front end to execute code in the background. The “background” is made up of multiple “layers” of code and it is split up into layers for very, very good reasons that have to do with good software architecture. You’ll typically find that applications have the “Application or Business Logic Layer,” the “Data Access Layer,” the “Data Layer,” etc. as shown in the graphic below.

This graphic depicts a “stack” of technologies and languages and shows what is arguably one of the most simple and minimal set of technologies that developers must know to even begin to barely call themselves full stack.

Things that are missing from the diagram include microservices (which breaks up the middle layers into separate servers), caching systems like Redis, event-driven technologies like Kafka, Docker containers, and all of the DevOps pipelines that need to be built out that compile, test, package, deliver, and deploy all of the pieces to Dev, QA, UAT, and Production environments.

A Full Stack Developer is a developer who is competent and experienced enough to work at any or all layers of the application from top to bottom including all the things mentioned above that are not depicted in the diagram.

Let me tell you from experience that … it takes a long time to reach that level of competency … and it is one of the most underappreciated skill sets of the tech world. But I digress.

Well, if achieving Full Stack level knowledge and skill is so great, then why are they at a disadvantage in a coding exercise? Because typically, Full Stack Developers don’t bother to memorize everything, or even to remain sharp, in every layer, at all times.

Because it’s not possible.

Every layer involves different technologies, and those technologies keep changing from version to version constantly. It’s just too much to keep up with.

In fact, there are people who specialize and make a career of staying in a single layer. Go do a search for “Front End Developer” on any job portal and you’ll see that it’s its own specialization. Full Stack Developers are a veritable one-stop-shop of technical services for every layer. So instead of trying to memorize everything, a different strategy must be employed.

Full Stack Developers concentrate on understanding the foundations, the concepts, and the computer science behind everything, and then utilize that understanding to figure things out and/or refresh their memory when it is needed for whatever layer they are called upon to work in.

In my experience, if I’ve been working somewhere in the back end for three months on a project, I begin to forget the details of the front-end framework such as Angular or React. If I work on the front-end for months, then I forget some details of the back end as well. But when I need to switch layers, I am able to refresh my memory and catch up within hours or a couple of days max. To do this, we don’t worry about every 20-line-of-code optimization. If we need to optimize something, we’ll dig into it as needed and solve the problem when it arises.

This is why live coding exercises tend to rock the chances of a Full Stack Developer. We don’t bother staying sharp in terms of depth on everything (but definitely some things). We provide value with our breadth of knowledge and get deep when we need to. Being sharp enough to code an optimal solution to a new problem in fifteen minutes is not our strength. We can do it when necessary, but it might take us 30 or 45 mins to regain our bearings. Ultimately, the time it takes a Full Stack Dev to re-establish depth is negligible relative to the great value they bring in the versatility they have by being able to jump from layer to layer and still be competent.

So, what’s the lesson here? Don’t be fooled if a Full Stack Developer doesn’t do particularly well in a live coding exercise. Or better yet, don’t use coding exercises at all. I may have mentioned that point before.

Live vs. Assigned Coding Exercises

An alternative coding exercise that doesn’t cause the ills mentioned above is an assigned coding exercise where the candidate has to implement a small project independently on their own time and then submit it when ready.

This is a much better option because it is closer to a real-world situation. It allows an interviewer to assess the candidate’s ability to design and implement a solution holistically. They’re not encumbered by the high-pressure live shadow, and it serves as a point of discussion to conduct the interview. The interviewer can ask why such and such design decision was chosen. They can ask the candidate to compare/contrast other methods and defend their choices. They can ask if they have considered any of the other ways to solve the problem. If they cannot that’s fine but maybe you’d reason that they’re close enough and with a little mentoring, they could be groomed into a next-level architect.

All of that is good but the glaring problem with this alternative approach, even though it is much better for the employer, is that it is a major burden for the candidate. Many candidates will go after the opportunity that will pay them the same with no need to code a project at all. Furthermore, the candidate faces the very real possibility that they’ll be rejected on the basis of what they produced without even a conversation, making it all a giant waste of their time.

The best candidates can find a job without being forced to build some project on their free time to make you oh so happy to slam the door shut on them. Take-home coding exercises are a huge risk for developers and the best developers don’t need those jobs. They can prove just as much for so many other employers and they’ll gladly take the path of least resistance.

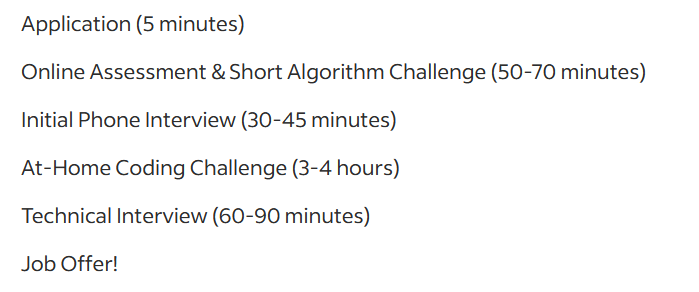

Here is a screenshot of a part of a job posting I found as I was writing this article that describes the interview process.

That is an example of what not to do.

The job description was good, the compensation was transparent, high paying, with robust benefits, a good bonus structure, and 100% remote. Excellent opportunity, until I saw the coding exercises, and knew that I would never apply for this job because of it.

What you need to come to grips with is that assigned, take-home coding exercises chase away the best candidates.

A Better Approach

Look. Just forget about coding exercises altogether. They’re simply not worth it. But I’d be doing you a disservice if I made you read this far without offering a better way.

The first way is the tried-and-true verbal interview. However, I wouldn’t just leave it at that. I wrote an entire article to guide you on that topic, which is the subject of the third and final part of this series.

But before you move on to the final part of the series, there is also a second way to get a lot of the answers you’re looking for from the dreaded coding exercise without requiring one. It’s like an interview hack. And that is by having the candidate produce one or more diagrams depicting their solution. Here you basically have the candidate design a solution and present it with diagrams instead of writing code.

Now, using this approach, you can have someone come up with a problem that is bigger in scope (i.e., an application or a part of an application) instead of being limited to a small problem that is constrained by the burdens of coding.

For applications built with Object Oriented Programming languages such as Java or C#, this can be done nicely with UML Class Diagrams. They should require only the boxes (i.e., classes and interfaces) without the details in them or only the most critical details in them (some important methods perhaps) and they should have the associations between them (inheritance hierarchies, dependencies, cardinality). Also, a database Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD) can be part of it, which doesn’t take very long to produce.

As a business stakeholder, you won’t be able to understand it but if you instruct the technical interviewer to produce and require these artifacts then you’ll get the best of both worlds. It won’t take long for a candidate to produce the diagrams (they can be sketched in a notebook), and it will reveal their understanding of software development principles at a much higher level. Finally, a robust interview can be conducted using the diagrams as subject matter for the interviewer’s line of questioning and ongoing discussion.

Require this approach only if you’re seeking an elite Software Architect. You shouldn’t require this of Senior Developers or below. If you don’t have a Software Architect guiding and providing oversight, then already you’re doing it wrong. Check out my previous article below for more insight on that point.

The Major Software Engineering Mistake That No One Is Talking About

Finally, the last thing I’ll warn you about if you (wisely) require diagramming in lieu of a coding exercise is that you should know that recruiters will collect the submissions from the candidates who failed and keep giving them to the next candidate in hopes that they’ll learn what not to do going forward.

To guard against this, the interviewer should come up with a problem that is sophisticated enough to require legit skills to design for and conduct a qualitative interview asking questions about the candidate’s reasoning, thought process, possible alternatives, etc. then do not reveal what is sought after during the interview. The diagrams could be good, but a skilled interviewer will know if the candidate produced them by researching during this type of interview. It is extremely hard to fake real architect skills. The diagrams being given to the next candidate won’t matter anymore.

Another way to guard against this is to come up with different problems and shuffle them between candidates from the same recruiter. You can reuse the same problem with candidates from different recruiters but switch them up for candidates from the same recruiter. For example, if you have five problems, you can give one different problem to five candidates and do the same for three different recruiters for a total fifteen candidates. Hopefully you’ll find a good hire in that pool.

A third way is to make the problem somewhat sophisticated enough but not so sophisticated that solving it would take more than an hour and then require the candidate to produce the diagrams in person on paper or whiteboard. I’ve been put through this sort of interview task before, produced my design on a whiteboard, passed the interview with flying colors, and was hired as a Software Architect where many had failed before me.

That was a lot but I hope this article contributes to good in this world by encouraging the demise of coding exercises in the hiring process for software developers, and I hope that you’ll move on to Part 3 of this series where I cover how to assess proficiency, competence, and skills.