The Business Stakeholders Guide to Hiring Software Engineers - Part 3

This three-part series is a guide for business stakeholders who don’t know how to conduct a technical interview for software development candidates. You don't need technical knowledge to benefit from being an observer in an interview.

This series reveals the talent acquisition hacks you need to hire the best software developers. They come in the form of a number of critical do's, don'ts, and guidelines that you should follow, which require no technical knowledge at all.

The three parts of the series are:

- Part 1: Never Allow Techs to Interview Candidates Alone

- Part 2: Avoid Coding Exercises

- Part 3: How to Assess Proficiency, Competence, and Skills

Here’s the challenge.

You have software developers reporting to you but you don’t have a coding background, so when the time comes for you to hire, you don’t know how to vet a software developer candidate. As a consequence, you’re forced to rely on currently employed software developers to conduct technical interviews for you. If this describes your situation then you’re in the right place.

This part of the series is my take on how you can wrap your head around assessing a software developers’ proficiency, competence, and skills.

Assessing Proficiency, Competence, and Skills

Let me begin with a little disclaimer. I’m going to stray a bit from the dictionary meaning of the terms proficiency and competence because this is the best way that I can explain it.

The concepts of proficiency and competence are often conflated. It is assumed that if a person is proficient that they are competent or that if they are not proficient, then they are not competent for the role. This is not necessarily true and the two concepts should be treated separately on their own merits.

To me, proficiency is largely a function of memory, which requires the basic recall of fact. If I had a photographic memory, I could probably impress people by reproducing facts, code snippets, or diagrams that I saw in a book. It could also mean that I’ve done it so many times that the information stuck and that proves that I am proficient and able to do the job.

But not all super coders are “proficient” in the sense that they can write code straight from memory.

For example, I don’t remember all the ways I can use PowerShell. I know what PowerShell is capable of and when I need to do something, I look up the relevant “commandlets,” then I follow the documentation to get it done. To understand what I mean, take a look at this list of PowerShell commandlets, scroll to see how gigantic the list is, then click on one or two of them to see the details, and tell me who can remember all of that without having to look it up?

Nobody.

When it comes to coding SQL on the other hand, I can produce rather complex stored procedures off the top of my head because I’ve had jobs where I coded so much SQL that it’s been etched in my memory and the features of the language aren’t nearly as numerous as the commandlet library of PowerShell.

So, with SQL I am proficient but with PowerShell I am competent … and that is enough.

You can be proficient with a language but not have a high degree of competency. There are many programmers who can code straight away and produce low-quality code that violates all manner of principles and best practices.

You can also be competent but not proficient where programmers don’t have the details memorized but they understand the patterns, best practices, and architectural principles. Even if they have to look up the syntax or details, they can produce high-quality code because of their elite foundational understanding.

When I interview candidates to test their proficiency, I will do so for those topics that the candidate claims proficiency or for those topics that they most recently utilized. I test for proficiency mostly to assess the candidate’s level of integrity. To me it is a measure of honesty. If they did indeed work full time coding in C#, for example, then they should know some things right off the top of their head.

You’d be shocked. I’ve tested candidates on the absolute most basic things that they claimed proficiency on and they could not answer those questions correctly. That tells me they were less than honest. If they answer correctly then I also test for competence. For other things, if they haven’t touched them in a while then I will forgive their lack of memory on the details but I will test them on their comprehension of the concepts (i.e., competence).

If you’re a business stakeholder observing a developer conduct an interview, you should be able to ask the developer the reasoning behind their line of questioning. Sometimes developers assume that a good memory means the candidate is competent when that is not necessarily true. If the candidate cannot remember the details but shows a solid grasp of the concepts then ask the developer how long it would take for someone to refresh their memory on the details. You’re likely to discover that the person can regain proficiency in hours, days, or less than a month. At that point, this is not a deal-killer but you would not know that if you’re unaware of the developer’s method of assessing the talent.

You could be missing out on a good hire because the interviewer expects proficiency when they should be looking for competence.

Here’s how you should be assessing a candidate’s level of Proficiency vs. Competence for a particular Skill.

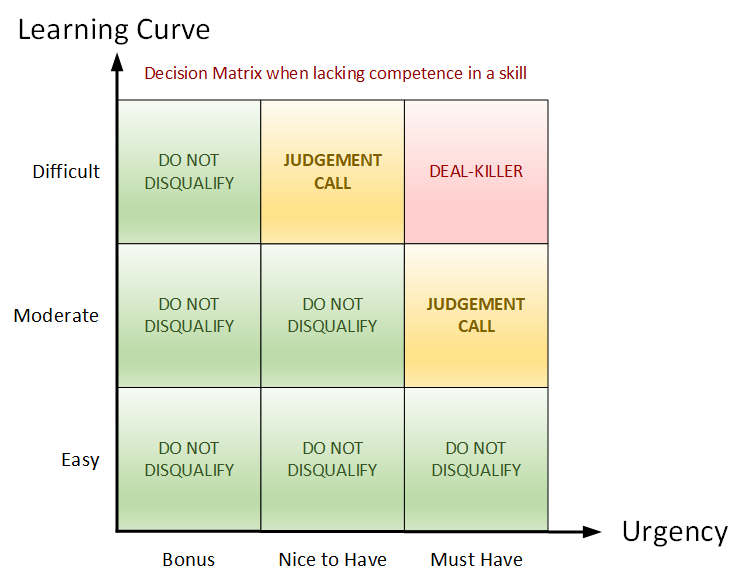

Consider the matrix below.

The left (y) axis represents how long it takes to learn a skill in terms of competence with increasing levels of difficulty. It is not about how long it takes to memorize stuff, but rather it is about how long it takes to acquire a high level of competence with that skill.

The lower (x) axis represents how necessary or desired that skill is with increasing levels of urgency.

The key to using this matrix is that it is a guide for deciding how to treat the candidate when they do not possess a high level of competence in that skill.

So basically, if it is determined that the candidate does not possess a high level of competence in that skill, is it a deal-killer? The answer is derived from plotting that skill on the matrix to get an idea if the lack of that skill is a deal-killer or not.

For each skill determine the following:

-

How difficult is it to master (be highly-competent in) that skill?

- Easy

- Moderate

- Difficult

-

How important is it for the candidate to have a high level of competency with that skill?

- Bonus

- Nice to Have

- Must Have

If the skill in question is:

-

Easy to Learn + Bonus to Have

- Don’t spend time on this in the interview. It can be communicated after the person is hired that it would be a bonus to acquire the skill. Since it is easy, this is reasonable to ask for and to achieve.

- Do not disqualify on this basis

-

Moderate to Learn + Bonus to Have

- Don’t spend time on this in the interview. Can be communicated after the person is hired that it would be a bonus to acquire the skill but may not be worth it.

- Do not disqualify on this basis

-

Difficult to Learn + Bonus to Have

- Ignore completely

- Do not disqualify on this basis

-

Easy to Learn + Nice to Have

- Can be mentioned in the interview but don’t spend much time on it. Communicate to the person after hiring that it is nice to have and should be reasonable to acquire the skill. They can either be encouraged or required to learn the skill.

- Do not disqualify on this basis

- Good to consider for performance reviews

-

Moderate to Learn + Nice to Have

- Can be mentioned in the interview but don’t spend much time on it. Communicate to the person after hiring that it is nice to have and encourage or require them to acquire the skill.

- Do not disqualify on this basis

- Good to consider for performance reviews

-

Difficult to Learn + Nice to Have

- If there is a strong desire for the candidate to acquire this skill then it should be a “Must Have” not a “Nice to Have.” Might need to require the candidate to grow so perhaps they should be somewhat competent with this skill but not zero. Have other team members groom/mentor the new hire over time until they acquire this skill.

- May or may not disqualify on this basis

- Judgement Call

-

Easy to Learn + Must Have

- Cover it thoroughly in the interview. If the candidate doesn’t have the skill, require that they learn it immediately. Since it is easy to learn, they should agree to this.

- Hire with the understanding that the candidate can/will acquire the skill as soon as possible

-

Moderate to Learn + Must Have

- Cover it thoroughly in the interview. If the candidate has some level of competence with this skill, consider hiring and require that they complete their learning as soon as possible. If the candidate has no exposure to the skill at all then do not hire.

- Do not hire if completely new to the skill

- Consider hiring if they have an adequate level of competence with a commitment to learn it immediately

- Judgement Call

-

Difficult to Learn + Must Have

- Cover it thoroughly in the interview and do not hire unless they have a strong level of competence in this skill. Organizations should have the means to groom and mentor lower-level team members by higher-caliber team members to graduate them into a high level of competence for this skill. For new hires coming in at the higher-level role, they should be competent.

- Do not hire if the candidate does not have a high level of competence in this skill already

- Otherwise, hire candidate into a lower-level position and mentor up if possible

- Deal-Killer

Often what happens is that interviewers report that the candidate didn’t know this or didn’t know that giving them a thumbs down, when the thing the candidate didn’t know is at least fairly easy to learn.

Here’s one story of my personal experience.

I started working with Angular when it was new, then for about a year I focused almost entirely on backend code and cloud infrastructure due to the nature of the project. By the time I moved on to another job and was interviewing, Angular 7 was released, which was five versions past what I had last worked with. Then on my job hunt I was tested on my front-end knowledge in an interview.

The guy who interviewed me was an expert and the questions he asked proved that my knowledge of front-end development was grossly outdated. I didn’t get the job but I never forgot the concepts that he touched upon and I made a mental note to catch up.

Eventually, I was hired by a company where I had a colleague who was a front-end developer, but he was more of a designer than a coder (although he could code pretty well for an artist). He was new to the company like I was and he explained that at his old job they used Angular + NgRx (Redux) and wanted us to implement the pattern. None of us knew what NgRx was but I took the initiative to look into it. What I found was that this happened to be the stuff the other guy interviewed me on that I did not know.

So, I read the documentation, took an online video course, followed tutorials, and basically immersed myself in it until I had a solid understanding of it, which took about three weeks. I started to implement the pattern and by the fifth week I had a successful implementation of Angular with Redux in our application.

Shortly thereafter, I became the resident expert on Angular+Redux and trained developers on it from our office as well as many from our headquarters in the UK. The training session was recorded and referenced multiple times thereafter.

The moral of the story is that not having a “Nice to Have” skill that was “Moderately Difficult” to acquire likely contributed to me not getting the previous job. They missed out on a person who rose to the occasion in three weeks, with no help, but I could have been a resource they enjoyed. If that guy who interviewed me had mentored me, he would have gotten me up to speed in probably half the time.

As the business stakeholder, you should be able to get multiple developers to explain the absolutely necessary skills, the nice-to-haves, and the bonuses along with their levels of difficulty to learn. If an interviewer sours on a person’s lack of competency with a particular skill and wants to disqualify them, make sure it’s not one of the “green” [Easy/Moderate] + [Bonus/Nice-to-Haves]. Otherwise, you could be missing out on a good hire that just needs a little time to ramp up, like almost everyone has to do, when they are new to a job.

Qualitative Interviews

Interviews shouldn’t be completely quantitative in nature. That is, they shouldn’t rely exclusively on checking boxes in yes or no fashion. There are nuances.

Interviewing should entail confirming and agreeing on the definitions of terminology. It should include understanding the reasoning for an approach. It should test for a capacity to conduct some form of cost/benefit analysis. Questions should start conversations and flow with follow-up questions all geared toward understanding mindset and where a person’s headspace is within a given context.

Interviewers should be open-minded and tolerant of other views. I’ve asked questions having different opinions about a candidate’s answer but focused more on their defense of it. For some things I’m more interested in their ability to posit a defensible position than I am in their agreeing with me.

This can be sort of philosophical, but it doesn’t have to be. Sometimes just having a casual dialog with a candidate can tell you more than questioning in a pop-quiz manner that essentially only tests for good memory. You don’t want to miss out on soft skills, cultural fit, and the greatest hallmarks of a good hire – integrity + creativity.

Existing Bodies of Work

Imagine if you could go to a candidate’s previous company, show up at their office, ask to speak to the previous manager, and say, “Hey I’m interviewing your previous employee and I’d like to see the code they wrote for you, the documentation they produced, their diagrams, or any other artifacts they produced.”

Then imagine that manager saying, “Of course come right in.”

Would you consider this good information?

I’ll wait.

Okay, I won’t wait.

You would be a complete fool if you didn’t emphatically say YES. Obviously, that would be great information if you could get your hands on the candidate’s previous work and look at it to make an exquisitely informed hiring decision.

Well, you’ll be shocked to know that many, many people along the hiring process have access to this type of information and then immediately dismiss it without so much as a glance.

It comes in the form of Open-Source Software contributions and Blog Articles.

They are treasures. They are nothing short of baskets of gold for the hiring manager. A cold bottle of water in the desert. A nail gun when building a treehouse. Beauty, money, humor, and charisma when searching for a spouse. A beacon when you’re searching for a lost Air Pod. An airplane when you need to cross the ocean. A flashlight in the dark. And a gun in a sword fight.

Recognize that it makes the decision to hire or not to hire orders of magnitude faster and easier. Think of all the interviews, the back-and-forth phone calls, emails, and text messages you can eliminate just by examining this information. Plus, you can have multiple people examine the information concurrently and at a convenient time of their choosing to get multiple streams of immediate feedback. It’s not often that you can say, “Well that entire hiring process could have been an email.” Do you understand how big this is?

But these artifacts of work are largely ignored.

Fools. Fools I tell you.

How do I know this happens? Because I have published open-source software and written articles (like this one), put links to them on my resume, and not a single recruiter or hiring manager has ever mentioned them to me during my job hunts.

I mean seriously. I hate to sound unprofessional in an article that I published for the world to see no less but it deserves for me to say … how stupid. Just … dumb. Omg … I’m just … smh.

If I’m evaluating a candidate and I see that they have a GitHub repository, I would immediately go there and bask in the trove of information that was gifted to me on a silver platter. Because I’m going to reach a thumbs up or down that much faster. Also, because people who publish open-source code tend to be the ones who are most confident and have more experience. So, there is a higher probability that those who make open-source contributions will turn out to be prized candidates.

So, for the sake of all that is good and holy, if you see a resume with open-source contributions, raise it to the top of the stack and do not ignore it. Make sure you look at it even if you’re a business stakeholder because you can assess their written communication skills, their ability to convey complicated information, and many other things. Then make sure a developer who can judge the code looks at it, ideally multiple developers, and get the necessary feedback.

You’re welcome.

In Short

Identifying good software developers doesn’t have to be difficult. You just have to know the strategies. Here’s a list of the points covered in this series

- Be present in the interviews and mentor developers on these concepts.

- Be aware that developers could have hidden biases and/or agendas that don’t serve the organization well.

- Warn them about the manipulations that candidates can employ.

- Make sure they ask questions that matter in the limited time you have in an interview.

- Forget about coding exercises – they are not as useful as they seem.

- Favor diagrams in lieu of coding exercises.

- Treat the concepts of proficiency (memory) and competence (understanding) differently.

- Use the skill decision matrix to ascertain whether the lack of a skill is a deal-killer.

- Use qualitative dialog with follow-up questions during conversation in the interview.

- Take full advantage of open-source contributions and articles published by the candidate.